ニューロダイバーシティとゲーム・ベースド・ラーニング──遊びの場がひらく関係性の再構築 / Neurodiversity and Game-Based Learning

*English follows Japaneseニューロダイバーシティとゲーム・ベースド・ラーニング──遊びの場がひらく関係性の再構築

渡辺ゆうか(慶應義塾大学SFC研究所 訪問研究員)

私たちは、学びの場において「違い」をどのように捉えているでしょうか。神経多様性(ニューロダイバーシティ)という言葉が少しずつ広まりつつある今、認知や文化のスタイルが異なることを、単なる「配慮」の対象ではなく、価値ある資源(アセット)として捉える視点が求められています。

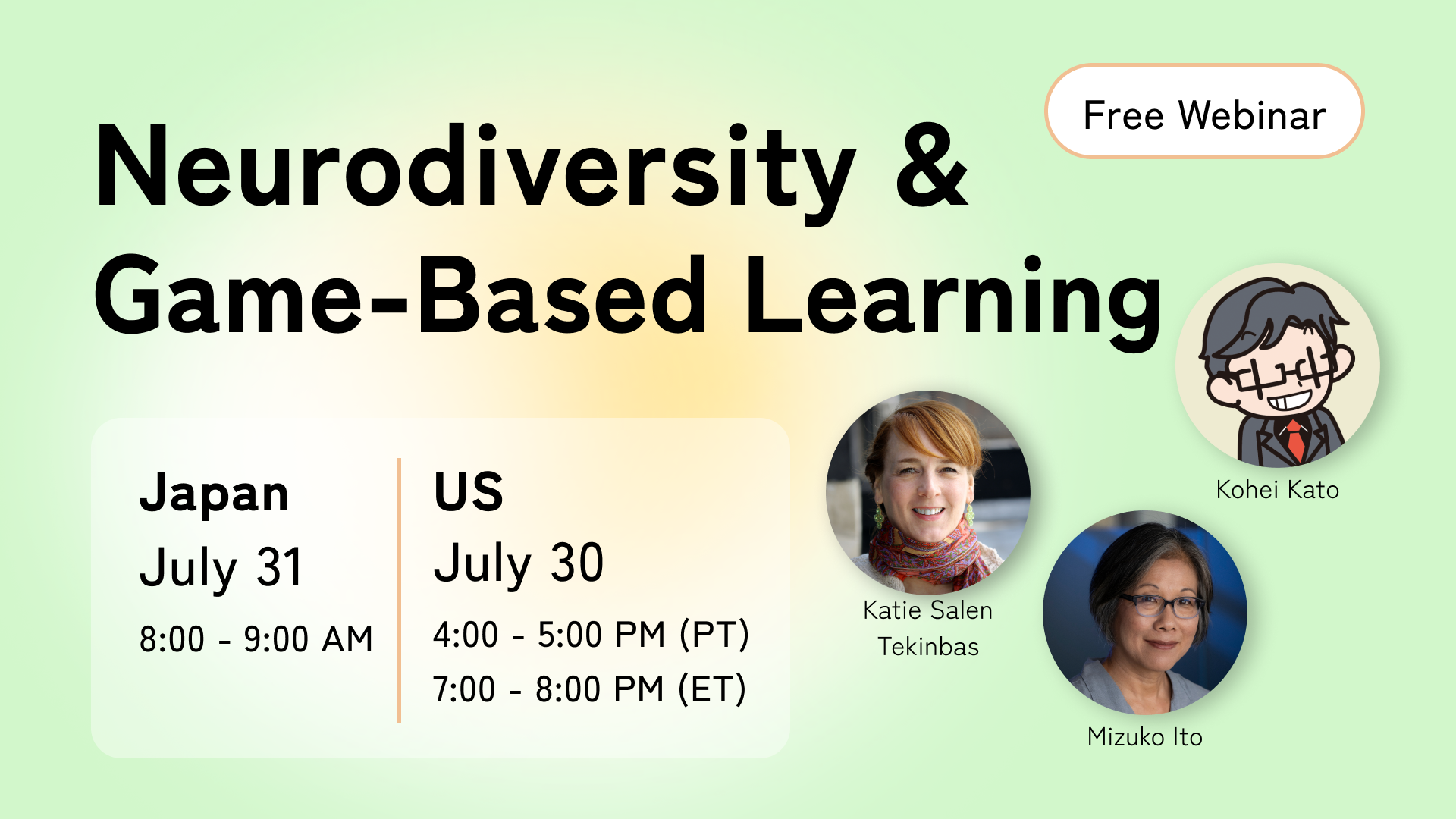

本ウェビナーでは、ゲームを媒介とした学びの場が、いかにして多様な子どもたちにひらかれたインクルーシブな空間となりうるのかをテーマに、二人の学者ー実践者を迎えて対話を深めていきました。ひとりは、ゲーム学習デザインの研究者であるケイティ・セイレン・テキンバシュ氏。そしてもうひとりは、神経多様な若者と物語を紡ぐ研究者・教育者の加藤浩平氏です。ファシリテートを伊藤瑞子氏が務め、異なる実践と文脈をつなぎながら、問いをひらき、共通項や可能性を見出していきました。

本稿は、2025年7月30日(日本時間7月31日)に開催された「ニューロダイバーシティ・ポテンシャル・スタディ・グループ(通称:NeuPoteKen)」第2回ウェビナーの対話とやりとりをもとに構成しています。

デジタル空間で自分らしく関わる

ケイティ・セイレン・テキンバシュ氏は、長年にわたってゲームデザインと学習、そして「遊び」の文化的実践に携わってきた教育者・デザイナーです。「ニューロダイバーシティそのものを専門にしてきたわけではない」と語る一方で、テクノロジーやゲームデザインの現場には、多くのニューロダイバージェントな若者たちが関わっている状況があるといいます。そうした気づきは、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校におけるゲームとインタラクティブメディアプログラムの教育現場で、神経多様な学生たちが自らの資産を活かしながら学びに関わる姿から得られたものでした。

また、彼女はゲームに基づいた学習を中心とするニューヨーク市の公立学校 Quest to Learnの設計に携わった経験も持ちます。2009年、設立時には、全校生徒のおよそ3割が特別なニーズを持つ子どもたちであり、学びの空間そのものが多様性に開かれた設計を求められていました。さらに、非営利団体 Connected Camps の共同設立者として、Minecraft や Robloxといったゲームプラットフォーム上で、8歳から15歳の子供と大学生メンターをつなぐオンラインプログラムの開発・運営にも力を注いでいます。Connected Camps でも特性がある子供とメンターが沢山参加しています。

ファシリテーターの伊藤氏はケイティ氏に、コロナ禍を経て対面活動が推奨される流れの中、デジタル空間での経験が子どもたちにいかなる肯定的効果をもたらし得るのかを問いかけました。ケイティ氏は、多くの子どもたちにとって、ゲームはもはや「キーボードに向かうゾンビ」という孤独な娯楽体験ではないと指摘しました。オンラインゲームは体験学習のための社会的空間を構築できるので、「特に若者がシステム、物語、社会的世界に没頭し、そこで意味を作り出し、リアルタイムで協働している時、深遠なものになり得る」と主張しました。

さらにオンライン空間は、地理的・社会的な制約を超えて「自分を理解してくれる仲間」と出会える場でもあります。学校や家庭では見いだせなかった共鳴できる相手とのつながりは、神経多様な若者にとって大きな意味を持ちます。ケイティ氏また、アバターやチャットなど多様なコミュニケーション手段の選択が「一般的な社会性のプレッシャー」を軽減し、神経多様性のある子どもたちの安全感や帰属意識の支援法にも繋がると説明しました。

物語の中で出会いなおす

加藤浩平氏は、自閉スペクトラム症(ASD)や発達障害のある若者とともにTRPG(テーブルトーク・ロールプレイングゲーム)を実践してきた研究者・教育者です。TRPGとは、3〜7人程度のプレイヤーが集まり、サイコロやキャラクターシートを用いて架空の物語を即興的に協働で作り上げていく会話型ゲームです。『ドラゴンクエスト』などのコンピュータRPGの源流にあたる遊びです。プレイヤーは自分の役割を持ち、ゲームマスターが導くストーリーのなかで意思決定や対話を繰り返します。TRPGの最大の特徴は、基本的に勝ち負けが存在しないことです。

加藤氏は月に一度開催される「サンデープロジェクト」では、このTRPGを通して子どもたちとの関係をじっくり育んでいきます。加藤氏が大切にしているのは「参加者全員が物語を心から楽しめたかどうか」にあります。ASDの子どもたちが社会的スキルをシミュレーションし練習するための手段としてゲームを使用する取り組みとは対照的に、加藤氏は「その場にいる仲間と物語を紡ぐ時間そのものを楽しむこと」を中心として考えています。「TRPGはソーシャルスキルトレーニングではなく、TRPGを楽しむことに意味がある」と語ります。そうして生まれるやりとりや笑い、ちょっとした驚きが、子どもたちの成長を自然に引き出していくといいます。その過程を、急がず丁寧に見守り続ける加藤氏の姿勢が、多くの共感を得ていました。

TRPGに参加したあるASDの青年のエピソードが紹介されました。最初、彼はどこかこちらを試すような態度で、ゲームマスターの呼びかけにも反応が薄く、自分の好きな話題を一方的に喋り続けたり、否定的な言動を繰り返したりと、協力的な姿勢とは言いがたい様子でした。そうした態度の奥には、おそらく10代のASDの子どもたちの多くが経験してきた、繰り返されるコミュニケーションの失敗や、「どうせ自分なんてうまくやれない」という静かなあきらめの感覚が、深く根づいている場合があります。

けれど、TRPGという遊びには、ユニークな構造があります。ひとつの物語を、仲間と共に紡ぎ進めていく。そこに明確な「正解」や勝ち負けはなく、たとえ少しふざけた発言であっても、物語のスパイスになるような“居場所”が用意されています。つまり、少しくらい非合理的でもいいし、ちょっと型破りでもいい。「自分らしさ」そのままで、物語に関わることが許される余白が、そこにはあるのです。ASDの若者にとって、これは自分らしさを隠すことなく、周りに合わないことを恐れずに参加できるということを意味します。

最初は茶化すような言動が目立っていた彼が、物語の展開とともに、仲間とのやり取りを楽しむようになっていきます。ある日、セッションの終わりに、それまで一緒に参加していた女の子に、こう言われました。「一緒に楽しく冒険できるようになったよね。」

彼は「ちょっと恥ずかしかったけど嬉しかった」と後で語っていたそうです。

ビギナー向けから始めるユニバーサル・デザイン

加藤氏が手がけた『いただきダンジョンRPG』や『ソウルキーパーズ』などのTRPGは、それまでTRPGにあった複雑なルールを取り除き、文章量を控えめにし、イラストなどの視覚情報を充実させた初心者向けの設計です。この工夫によってASDの参加者を支えるのと同時に「どんな子どもでも参加できる」インクルーシブな場が実現しました。神経多様な若者のために特化したわけではなく、「初心者が入りやすい」デザインが結果的にあらゆる人に開かれた場をつくり出しています。ルールの簡素化、イラストの多用、親しみやすい世界観の導入は、まさにユニバーサル・デザインの発想です。シンプルになったルールブックは、時にプレイヤーがゲームマスター以上に読み込むほど。ディスレクシアやディスグラフィアの子どもたちが参加する場面もあります。

ケイティ氏も、ゲームを初心者にとってアクセシブルにすることの重要性を強調しました。彼女は、子どもが好奇心を持ち、信頼を築くために、ゲームの最初の5分間で「子どもが求められ、安全で、自分らしくいられると感じる」ことを実感させることの重要性を協調しました。ゲームと学習の研究者がゲームをデザインする際に、学習成果をゲーム体験の原動力として重視しすぎていると見ています。そうではなく、デザインの焦点は「プレイヤーがプレイの瞬間に入ってくる時、そしてその最初の瞬間を、多様性を含めた人間として彼らを本当に見る方法でサポートする」ことを想像することに置くべきだと考えています。

子どもたちにとって、ゲームは単なる遊びの場ではありません。そこは子どもたちの存在が許され、自分らしい表現が歓迎される、「関係の入り口」となる場所です。加藤氏のTRPGクラブでプレイヤーとして参加を始めた子どもたちは、やがてゲームマスターへと役割を広げ、その後、自分自身でコミュニティを立ち上げたり、職場でボードゲームクラブを作ったりするようになりました。これは支援を受ける立場から他者を支援する立場への変化を表しています。こうした事例は、学びとエンパワーメントの理想的なかたちといえるでしょう。このような自然で繊細な成長プロセスこそが、ユニバーサルデザインを形作っていくのかもしれません。

どのように評価するのか

ウェビナー後半では、「このような活動をどのように評価すべきか」という問いが、参加者から投げかけられました。学力テストや数値的な成果指標では捉えきれない、TRPGやデジタルゲームの効果をどのように可視化し、何をもって「意味のある学び」と判断するのか、その評価軸をどこに置くべきかが問われました。

加藤氏は、これまで実施してきた定量的研究では拾いきれなかった変化や感情を捉えるため、近年はインタビューなどによる定性評価へと研究の方法を移行しています。また、子どもたちにとって、よりシンプルで本質的な指標のひとつが、参加者のこんなひと言に尽きるのかもしれません。

「また来たいと思う?」

子どもがもう一度その場に戻りたいと思えるかどうか。そして、実際にまた参加して同じ時間を共にする。そうした時間の積み重ねが、活動の価値を物語っているとも言えます。そうした時間は安心感に満ち、心を動かす体験であったかどうかを示しているものに違いありません。

ケイティ氏と伊藤氏は、個々のプレイヤーが経験することや成長・発達の仕方を評価するだけでなく、文脈やコミュニティの特性を評価することの重要性も強調しました。ケイティ氏は、自身のマインクラフトプログラムにおいて、子どもたちにコミュニティ意識や帰属感があるか、新参者と既存の参加者の両方が意味のある貢献をする方法があるか、そして安全感と帰属感があるかを重視していると述べています。神経多様性を持つ個人の学習と発達を支援するだけでなく、学習環境そのものを様々な特性を持つ人々が参加しやすいインクルーシブなものにしていくことが重要なのです。

主体性、エンパワーメント、そしてシステム変革

ケイティ氏は次のように振り返ります。「この仕事で私が本当に好きなのは、子どもたちの興味に寄り添い、ありのままの自分でいられるようにすることです。自閉症スペクトラムの子どもたちは、好きなことにとことん没頭する傾向がありますが、普段はそれを控えるよう言われがちです。しかしゲームなら、彼らが思う存分没頭できる環境を作れるのです。」ケイティ氏はゲームデザイナーや遊びの研究者としての経験を活かして活動を続けています。ゲームの重要な点の一つは「いろいろなことを試したり、普段とは違う自分を演じたりできる遊びの場」だということです。

ケイティ氏は、本来興味のないこと(ソーシャルスキル訓練など)をするためにゲームを使う「ゲーミフィケーション」の一部のアプローチとは異なり、ゲームを「プレイヤーのための空間」として使う加藤氏のアプローチを評価しています。「彼らには、どのように参加したいか、どのように自分を表現したいかを選ぶ権利があります。」加藤氏も、主体性とエンパワーメントの重要性を強調しています。「支援される側が、やがて“支える側”へと立場が変わること。それ自体がエンパワーメントであり、社会参加の1つの形だと思うのです」と語ります。

そしてそれは、TRPGにとどまらず、子どもたちが安心して関われる多様な場であり、多様な選択肢が地域のなかに編み込まれていくことを意味しています。そうしたひらかれた構造こそが、神経多様な子どもたちにとっての「自由」につながるのだと。「特別な配慮」を制度のなかで保障するのではなく、多様な関わり方が社会の中にあってよいのだという風通しのよさが、神経多様性という概念が私たちを取り巻く社会に問いかけていることなのかもしれません。

解を急がず、問いとともに関係性を編み直していく

本セッションのファシリテーターを務めた伊藤氏は、「教育とは、個を変えることではなく、その人の持ち味が自然に立ち上がる“関係性の土壌”を編むこと」だと語ります。

私たちは、子どもたちの「変化」や「成長」を語るとき、その背景にあった環境や関係性を、どれだけ丁寧に見つめているでしょうか。誰かの可能性を引き出したのではなく、すでにあった力が自然に立ち上がるような余白を、そこに用意できていたのかどうか。その問いこそが、ニューロダイバーシティの実践を照らす灯火なのかもしれません。

ニューポテ研の試みは、まだ始まったばかりです。MinecraftやTRPGといった「遊び」に根ざした実践、そして登壇者たちが持ち寄った多様なまなざしと現場の声は、「解」ではなく「問い」から始まる学びの可能性を私たちに示してくれました。正しさを追い求めるのでなく、誰かを変えることを急ぐのでもなく、違いをそのまま携えながら、ともに考え、ともに編みなおしていくこと。そのような新たな関係性の編み直しこそが、これからのニューポテ研の探究の歩みを力強く支えていくのだと思います。

ニューロダイバーシティ・ポテンシャル・スタディ・グループ(NeuPoteKen)は、ニューロダイバーシティやコネクテッド・ラーニングに関心をもつ日英両言語圏の研究者・実践者・デザイナー・政策決定者のコミュニティです。本活動は、東京のNPO法人ニューロダイバーシティ、千葉工業大学変革センター、コネクテッド・ラーニング・ラボ、コネクテッド・ラーニング・アライアンス、金子総合研究室、一般社団法人国際STEM学習協会、ファブラボ鎌倉などの連携のもと運営されています。参加希望・お問い合わせは info@neupote.orgまでご連絡ください。

Neurodiversity and Game-Based Learning – Reconstructing Relationships Through Play Spaces

Youka Watanabe (Visiting Researcher, Keio University SFC Research Institute)

How do we perceive "differences" in learning? As the concept of neurodiversity gradually spreads, we need to see different cognitive and cultural styles not only as demanding "accommodation," but as valuable assets.

This webinar explored how game-based learning spaces can become neurodiversity inclusive environments. We welcomed two scholar-practitioners for deep dialogue: Katie Salen Tekinbaş, a game-based learning researcher and designer, and Kohei Kato, a researcher and educator who creates stories with neurodiverse youth. Mimi Ito facilitated the session, posing questions and exploring commonalities and connections.

This essay is based on the dialogue from the 2nd webinar of the "Neurodiversity Potential Study Group (NeuPoteKen)" held on July 30, 2025 (July 31, Japan time).

Engaging Authentically in Digital Spaces

Katie Salen Tekinbaş is an educator and designer with a long history of work in game design, learning, and the cultural practices of play. Although she has not worked specifically in the area of neurodiversity, she has seen how many neurodivergent people are involved in her fields of technology and game design. She engages with many neurodivergent students in the Game Design and Interactive Media program at UC Irvine, and she has worked to build on their strengths in developing curriculum and learning experiences.

She also led the design of the New York City public school centered on game-based learning, Quest to Learn. At the time of its founding in 2009, approximately 30% of Quest to Learn students were considered to have special learning needs, so the teaching and learning environment had to be designed in a neurodiversity inclusive way. She is also co-founder of the nonprofit Connected Camps, where she has developed and operates online programs that connect youth aged 8-15 with college student mentors on game platforms like Minecraft and Roblox, which also includes many neurodivergent children and mentors.

Mimi asked Katie about how she advocates for the positive experiences that kids can have online, particularly given the priority placed on in person activities after the COVID pandemic. Katie pointed out that for many children, games are not solitary entertainment experiences where they are “zombie kids on keyboards.” Online games can be social spaces for experiential learning that “can be incredibly profound for young people, particularly when they are immersed in systems, in stories, in social worlds where they are making meaning and collaborating in real time.”

Furthermore, online game spaces allow youth to meet other players who “get them or are like them," beyond geographical and social boundaries. For neurodiverse youth, finding connections they couldn't find with peers at school can hold great meaning. Katie also describes how diverse communication modalities such as online avatars and chat can reduce the “pressure to perform in normative ways,” supporting feelings of safety and belonging for neurodivergent children.

Building Relationships Through Stories

Kohei Kato is a researcher and educator who develops Tabletop Role-Playing Games (TRPG) programs for youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other developmental disabilities. TRPGs are social games where 3-7 players gather to create fictional stories in a collaborative and improvisational way, using dice and character sheets. It is the game genre that digital RPGs like Dragon Quest are based on. Players have unique characters and roles and make decisions and engage in dialogue within the context of a narrative guided by a game master. One of the most unique qualities of TRPGs is that there are no winners or losers.

Kohei nurtures relationships with children through monthly TRPG gatherings in the “Sunday Project." He feels it is critically important that "all participants are genuinely enjoying the story." In contrast to many efforts using games for autistic children to simulate and practice social skills, Kohei sees TRPGs as “inherently valuable as enjoyable time weaving stories together with peers." In other words, "TRPG is not social skills training; there's meaning in enjoying TRPG itself." He patiently nurtures the interactions, laughter, and small surprises that emerge, which support children’s growth and development over time.

Kohei described his experience with one autistic young man who had a somewhat antagonistic attitude when he first started playing TRPGs with the group. He wasn’t responsive to the game master's guidance, talked continuously about topics only he was interested in, and was repeatedly confrontational. This kind of antagonistic stance can grow from repeated communication failures that autistic teens have experienced previously, paired with a sense of resignation that they will never succeed socially.

However, TRPGs have a unique structure of weaving and advancing a story together with other players. The game lacks “correct answers,” winners and losers, and even cheeky remarks can find their place in the shared story as an unexpected bit of spice. It's okay to be a little random or unconventional. There's space to engage with the story authentically, just as you are. For autistic youth, this means they can bring their full selves to the table, without fear of not fitting in.

This young man who initially mocked his fellow players, gradually began enjoying interacting with his peers as the story developed. One day, at the end of a session, a girl who had been participating with him said: "We've become able to enjoy adventures together, haven't we?" He later shared that “I was a little embarrassed, but happy.”

Centering Beginners in a Universal Design Approach

In creating Itadaki Dungeon and Soul Keepers, Kohei simplified rules, reduced the amount of text, added more illustrations, and incorporated references from everyday life to make them more accessible to beginners than existing TRPGs. These changes not only supported the autistic youth who were playing, but also created a more inclusive game where "any child can participate." His goal was not to design a game specifically for neurodiverse youth, but rather to design for beginners in order to create a game that is inclusive for everyone. Players sometimes read the simplified rulebooks more thoroughly than even the game masters. Children with dyslexia and dysgraphia also found the revised version of the game easy to participate in

Katie also emphasized the importance of making games accessible to newcomers. She has found that ensuring that “a kid is going to feel wanted and safe and themselves" in the first 5 minutes of a game is critical, in order to support their curiosity and to build trust. She sees games and learning researchers who design games often putting too much emphasis on learning outcomes as the driver of the opening game experience. Instead, the design focus should be on envisioning "the player coming into the moment of play, and how to scaffold those initial moments in ways that really see them as humans, in all their diversity.”

For children, games can become not just places of play, but entry points for new relationships that affirm their identities, and create possibilities for self-expression. Children who started as players in Kohei’s TRPG club have moved on to become Game Masters, starting their own communities or creating board game clubs at workplaces. Those who receive support eventually shift to supporting others. These stories illustrate how small entry points represent the critical first steps towards universal design that supports learning and growth.

How to Evaluate

In the latter half of the webinar, participants raised the question about evaluation. How can we make visible the impacts of play with games and TRPGs without relying on traditional tests and quantitative measures? What counts as meaningful learning? What do we value as outcomes?

Kohei has shifted his focus to qualitative evaluation through interviews to capture changes and emotions that couldn’t be captured through qualitative surveys. He boils down the most important indicator as the answer children give to the simple question, "Do you want to come again?" He sees whether children want to return and participate again, and the ongoing influence of being in safe and engaging experiences as the key measure of the activity’s value.

Katie and Mimi also stressed the importance of evaluating not only what individual players experience and how they grow and develop, but also the characteristics of the context and community. Katie describes how in her Minecraft programs she looks at whether the kids feel a sense of community and belonging, whether there are ways for both newcomers and established participants to contribute meaningfully, and that there is a sense of safety. It’s critical to support not only the learning and development of neurodivergent individuals, but to also consider ways of making learning environments more neurodiversity inclusive.

Agency, Empowerment, and Systems Change

Katie reflects, “what I really love about this work is that it leans into the interests of the kids, and it lets them be whoever they want to be. Kids on the autism spectrum, sometimes they go really deep into interests, and often they’re told not to do that… but with games you’ve set up a space where it’s actually very natural for them to go deep.” She goes on to draw from her experience as a game designer and play researcher. One of the important things about games is that they are “a space of play where players are allowed to try different things, to be different people.”

Katie notes that unlike some approaches to “gamification,” which are more about using games to push kids to do things they aren’t otherwise interested in (like social skills training), she appreciates Kohei’s approach which uses games as “a space for the player. They have the right to choose how they want to show up, how they want to represent themselves.” Kohei also stresses the importance of agency and empowerment. "When those who are ‘supported’ eventually shift to becoming 'supporters'—that is empowerment and social participation."

It’s critical that children have access to diverse community spaces where they can be safe and explore a wide range of choices, in TRPGs and elsewhere. These experiences lead to freedom for neurodiverse children. The concept of neurodiversity insists that society changes to embrace these kinds of spaces, moving beyond a model of "special accommodation" within existing systems.

Reweaving Relationships with Questions, Without Rushing for Solutions

Mimi argues that "it’s incumbent on the environments to change even more than it’s incumbent on the individuals to change." When looking at "change" and "growth," are we observing the environment and relationships that are part of the learning context? Did we prepare an environment where existing strengths became visible, rather than developing new growth? These may be questions illuminating neurodiversity-informed educational practice.

NeuPoteKen’s exploration has just begun. Practices rooted in play like Minecraft and TRPG, and the diverse perspectives of our panelists showed us the possibility of learning that begins with questions rather than right answers, not rushing to change someone, but thinking together while embracing differences. Weaving together new relationships in this way will be essential for our future NeuPoteKen journey.

The Neurodiversity Potential Study Group (NeuPoteKen) is a community of researchers, practitioners, designers, and policy makers interested in cross-cultural dialogue between Japanese and English-speaking communities on topics related to neurodiversity and connected learning. It is part of an ongoing collaboration between the Neurodiversity NPO in Tokyo, Center for Radical Transformation at Chiba Tech, Connected Learning Lab, Connected Learning Alliance, Kaneko Lab, Global STEM Learning Association Japan and FabLab Kamakura. Please email info@neupote.org to inquire about joining NeuPoteKen.